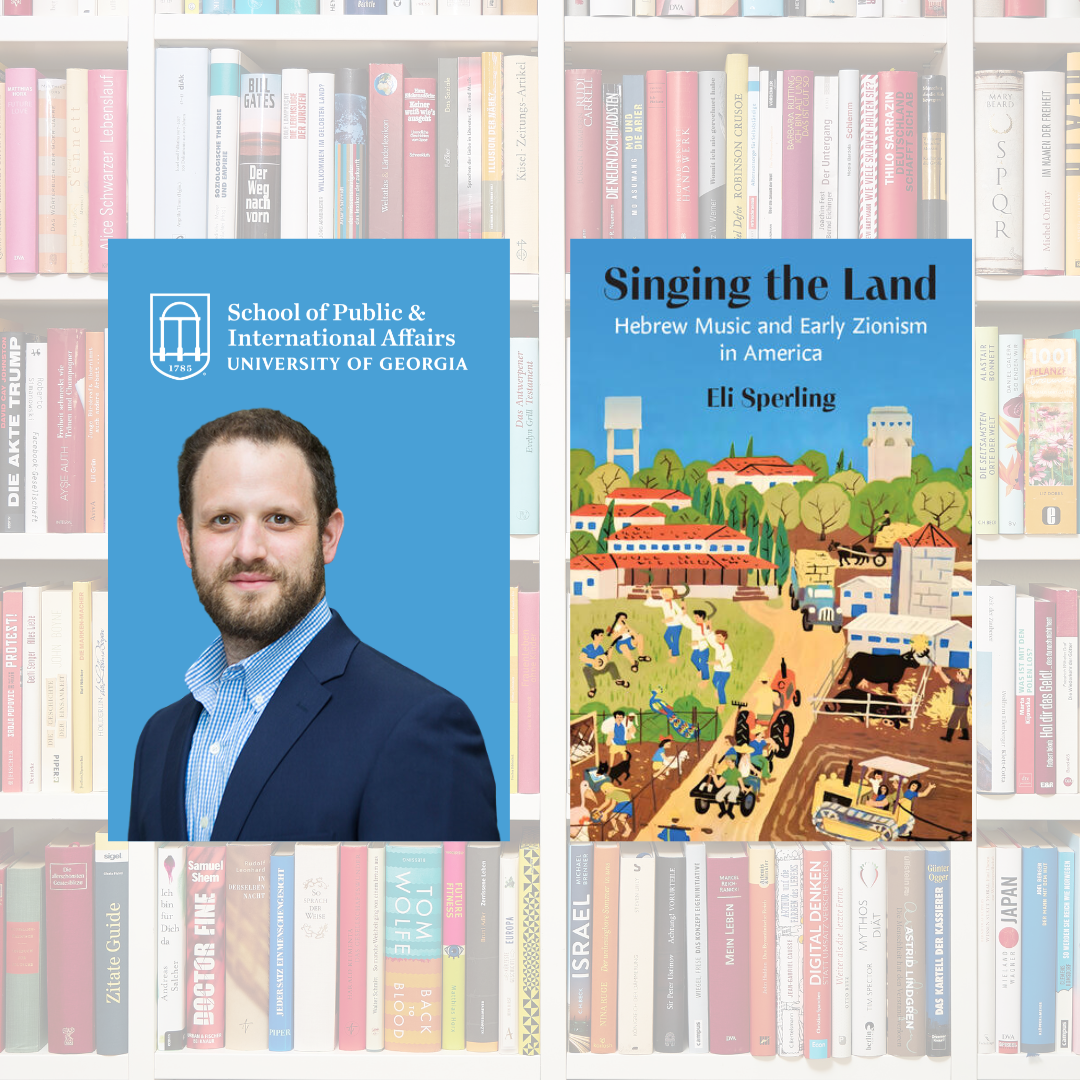

Dr. Eli Sperling, the Israel Institute Teaching Fellow in the Department of International Affairs, released his new book entitled Singing the Land: Hebrew Music and Early Zionism in America, in which he examines the extent to which popular Hebrew Zionist music connected the early-twentieth century American Jewry to the Jewish state. Sperling further illuminates the scope of his book in his answers to the questions below.

What role does Hebrew Zionist music play in American Zionism today?

Today, despite American Jews’ general lack of fluency in modern Hebrew, Israeli music endures as a central source of America’s diverse Jewish communities’ cultural connections to Israel and the modern Hebrew language. American Jewry engaged with aspects of Hebrew national culture, modern Hebrew language, and Zionist notions of Jewish heritage through song in pre-1948 America. And today, Israeli music remains a mainstay of religious, pedagogical, and communal approaches to strengthening the American Jewish community and its ever-changing relationship with Israel—as well as her national culture and institutions—occupying a strikingly similar role as it did a century ago. It is significant to note that many diasporic groups in America engage with homelands, source languages, national identities, and a variety of transnational religious groups through different music forms and traditions. Indeed, Singing the Land is a novel contribution to scholarship on Hebrew national culture, Zionism, and American Judaism pre-1948. Yet it sits within a much broader and still developing body of scholarly work seeking to analyze diasporic and transnational identities around the globe through music.

What influenced you to research the proliferation of popular Hebrew Zionist music in 20th century America?

Hebrew music produced in Palestine was a significant tool utilized by Zionists as they sought to evolve Hebrew national culture in Palestine prior to Israeli statehood in 1948. While beginning the research for this study as a doctoral student, I initially intended to investigate Zionism’s evolution in the Jewish community in pre-1948 Palestine through analyzing Hebrew music and national culture’s evolution there. Then, as I began to collect such musical sources from Palestine in the archives, I came across a dozen or so boxes of Zionist Hebrew song publications from pre-1948 America in a small music archive in the basement of Tel Aviv University’s library. Many were in English and/ or contained English translations. I was quite intrigued by the find, particularly since my doctoral committee and I were unaware that such American publications even existed. I soon discovered that during the first half of the twentieth century, dozens of Zionist Hebrew songbooks were produced in the US and Palestine for American Jewry’s consumption in the pre-1948 period. Through analyzing the integration of this music and Zionism more broadly into American Jewish life, I uncovered an underexplored story of Zionism, Hebrew national culture, and music’s parallel evolutions in America during the interwar period. Further, Hebrew song in America proved to be a vivid lens to analyze many American Jews’ negotiations between their place in American society, culture, and her economy with their growing pride in Jewish national developments in Palestine and then Israel. Indeed, American Jewry during this period sank their figurative plows into the soil of Palestine as they sang, listened and/ or danced to Zionist songs all while establishing frameworks for American Zionism and its ties to Jewish education, institutions, religious practices, rituals, and identity.

Was Hebrew Zionist music ever shunned in certain American neighborhoods during the time period?

Despite Zionism and Hebrew national culture’s (including songs) often-polemical nature amongst American Jewry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Zionist association and support grew to become mainstream in American Jewish life by the late 1930s and early 1940s. In the first decades of the twentieth century, Jews and Jewish leaders in the US, particularly within the Reform Jewish movement, were hesitant to endorse the idea of a Jewish national home in Palestine, let alone the adoption of any extra-American national identity or culture. However, by the 1920s, mainstream American Jewish embrace of and enthusiasm for Zionist engagement and Hebrew national culture (including songs) grew rapidly, as did the singing of Hebrew Zionist songs as a symbol of support for and comradery with Jews in Palestine. Yet, by the late 1930s, non-or anti-Zionist stances in American Judaism waned quickly amidst worsening circumstances for Jews in Europe and Palestine, barred by Congress in 1924 from seeking refuge in America. Then, alongside the outbreak of WWII and news of the Jewish Holocaust in 1942, public support of Zionist national goals in Palestine and then Israel, as well as singing Hebrew songs became central to American Jewish life, education, and identity.

Are there any hallmarks in Zionist history that have made Hebrew music what it is today to Americans?

One example of American Zionism’s rapid normalization in the 1940s occurred in 1943 with the publication of Selected Jewish Songs for Members of the Armed Forces. The songbook for American Jewish GIs contained many Zionist Hebrew songs (amongst numerous Jewish musical forms) and was seemingly designed to fit into the coat pocket of a US military uniform. A joint effort between the American Association for Jewish Education, The National Jewish Welfare Board, and the United Service Organization of America, the book contained the Zionist national anthem “Ha’Tikva,” which was placed just before the “Star-Spangled Banner.” While this shows the reality in the early 1940s, it represents a slow process while evolved through the interwar period.

Why should someone read your book?

Singing the Land explores the history, events, contexts, and tensions that comprised what may be termed the ‘Zionization’ of American Jewry during the first half of the twentieth century. It places novel primary sources within the parallel contexts of Zionist national development, the evolution of American Jewish life, the migrations, and circumstances of European Jews, as well as trends in national diasporic music culture more broadly amongst other immigrant groups in America. Through this analysis, Singing the Land offers engaging insights into how and why many musical frameworks for incorporating aspects of Zionism into American Judaism established during this period succeeded. By the mid-1940s, much like today, many American Jews, across denominations, supported the Zionist cause, even as a central component of their American Jewish identity. They did so while remaining firmly committed to their American locale and national identities, embracing their growing inclusion into Americanness and the American middle class. The proliferation of this widespread American Jewish-Zionist embrace was achieved through a variety of educational, religious, economic, and political efforts to build and then sustain the varying components of American Zionism as they evolved, and Hebrew music was a thread consistent amongst them all.