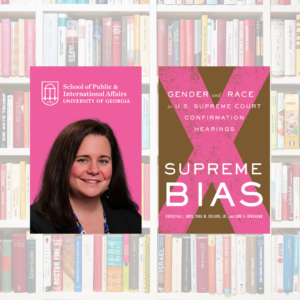

Dr. Christina Boyd, UGA Professor of Political Science and Thomas P. & M. Jean Lauth Public Affairs Professor, co-authored a book entitled Supreme Bias: Gender and Race in Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings, in which she and other researchers discuss behaviors observed within the US Senate Judiciary Committee when approving judicial candidates of various identities, specifically race and gender identities. Dr. Boyd further illuminates the scope of her book in her answers to the questions below.

What influenced you to research dynamics of race and gender at the Supreme Court confirmation hearings?

We were brought to this research project for a number of reasons. I have been studying the effects of judge gender and race on decision making on courts for years. My coauthors Paul Collins (University of Massachusetts) and Lori Ringhand (UGA Law) are some of the preeminent experts of Supreme Court confirmation hearings in the U.S., and their prior work highlights the importance of the hearings and the dominance of politics within them, among other things. Examining race and gender during the judicial selection process was a natural next step for each of us. With very recent historic confirmation hearings for (now) justices Amy Coney Barrett (2020) and Ketanji Brown Jackson (2022), combined with evolving public discussion about race and gender in courts and political institutions, this is a perfect time for our book’s release.

What are the main takeaways a reader can expect from your book and why is it important?

In our study of Supreme Court confirmation hearings from 1939-2022, our analysis reveals that female and person of color nominees receive a different confirmation process than do their white, male counterparts. This appears in a few notable ways during senators’ questioning of prospective Supreme Court justices. Women nominees receive more questions about their competence to serve on the Supreme Court. Also, both women and person of color nominees are subject to higher levels of interruptions from senators, more questions about their expertise in gender or race-related issue areas, and higher levels of words that are negatively-toned or designed to cast doubt on the nominee.

The presence of this unequal treatment of some nominees based on their race and gender matters a great deal. As we talk about in the book, filling Supreme Court seats is an important legal, political, and public event. The public closely watches these hearings and draws conclusions about our political institutions, our courts, our justices, and what behavior is appropriate in society. The stakes for Supreme Court confirmation hearings are incredibly high for senators, nominees, and the American public. Confirmed Supreme Court nominees serve on the court for decades and help craft national law and policy for the United States during the years of their service.

What were some of the research methods you employed for this project?

Our research relies primarily on an original dataset of around 38,000 transcribed statements made by senators and nominees during confirmation hearings from 1939-2022. We code those statements for the identity of the speaker, the issue area(s) being discussed, whether there is an interruption, the tone of the statement, and much more. We supplement these quantitative data with rich theory and qualitative data to provide a wholesale story about race and gender during the confirmation hearings across time.

Why is the Senate Judiciary Committee so susceptible to women and people of color receiving different treatment during their confirmation hearings?

Because the confirmation hearings take place in the Senate and the stakes are so high for Supreme Court vacancies, there are bound to be political dynamics at play, where Democratic senators are more skeptical of Republican presidents’ nominees and vice versa. Within that politically-charged confirmation environment, senators’ skepticism may be particularly high toward nominees that they are less familiar with—historically, women and person of color nominees of a senator’s opposite party. As we argue in our book, senators may not even realize they are treating nominees differently in the ways our data indicate.

Is there a path toward more equal treatment of women and people of color during future Supreme Court confirmation hearings?

Yes, I think there is. A couple of things will likely be particularly useful going forward. First, awareness will help. As the senators become more aware that they are treating nominees differently based on race and gender, they may well look to curb their behavior to help ensure that all nominees are questioned and treated in similar ways. Second, we will also likely see positive changes as the Senate Judiciary Committee grows in the number of women and people of color represented on it.